Sunday, June 29, 2008

Equal Footing back in action after hospital detour

Departing our hostel around midnight, we found our way to a public E.R. characterized by abysmal care, dried blood on the bedsheets, and prices so low Wal-Mart would be envious. By 2:00 am we were arguing our way into a private clinic which, though better on every dimension, was still BYOE -- Bring Your Own Everything: blankets, towels, bandages, drugs, needles, syringes, IV, bribes, and, of course, your best marketplace haggling skills to bargain over the price of health care. Neoliberal health care is a beautiful thing.

Since I am an inspiring role model, Nicole naturally followed my example and also got quite sick, though she was not sufficiently ambitious to be hospitalized. Probably because she was spooked by the witches' covey of evil eye nurses that cast a hex on her for breaking all kinds of hospital rules:

1) Thou shalt not sit on the beds (have to keep them pristine for non-existent patients).

2) Thou shalt not sleep on the beds either (even if not sleeping means you'll soon be a patient due to exhaustion)

3) Thou shalt not sleep period, even if you are a patient (direct quote: "This is a hospital. There's too much going on for you to sleep").

And so on.

The hospital also proved to be an educational forum through which to learn about racism in Sucre. The head doctor set the tone with "I'm not a racist, but those indios and their president are destroying our country."

Other than time spent hunting down witches, I mean nurses, we spent time learning about the prevalent racism in Sucre. Unlike some of the women in El Alto that we met, who fault Evo Morales for not going far enough in his nationalization projects, many Sucrenos hate Evo because he is moving away from privatization and also because he is indigenous. There is deep resentment towards Evo, his political party MAS )Movement towards Socialism), and the indigenous population in Bolivia in general. Racist graffiti lines the pristine walls of this colonial city, which has been named a UNESCO world heritage site, and racist comments about "those Indians." There's a reason that there's graffiti in La Paz stating "Sucre: the capital of racism."

The most stark example of this racism occured on May 24 of this year, when some powerful Sucrenos forced indigenous leaders to walk through the streets of Sucre on their knees, cursing at them and forcing them to renounce their commitment to Evo Morales (the first indigenous president in this overwhelmingly indigenous country). Faces were shoved onto the Bolivian flag as the leaders were beat up and called racist and derogatory names.

Not everyone in Sucre is like that, of course. We had lunch with a wonderful leftist professor who is part of a group to counter racism in their city. She described the climate of fear and political repression prevelant in Sucre. (She also brought us soup to our hostel!)

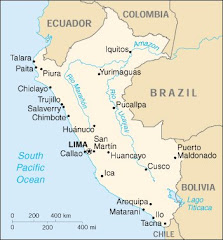

Now we're back in action in La Paz/El Alto, ready for our last week of Bolivian fieldwork before heading to Lima for a week. It's always adventurous in the Andes...

Pablo and Nicole

Tuesday, June 24, 2008

Transitions

But first, to back up a few days. On Friday night, Cesar and I went with group of 40 people to celebrate the Aymara (the largest indigenous group in Bolivia) New Year, leaving La Paz at 10pm and arriving in a very isolated village in the Bolivian altiplano (high flatlands) about 3 hours away at 2am. We arrived in the village and the sky was huge above us, an open expanse with very, very chilly winds making me glad I was wearing three pairs of wool socks. From 2am to 7am we took part in the rituals for the Aymara New Year, which consist of chewing coca leaves and making wishes on small figurines and coca leaves. Males and females were divided, and put our wishes into separate offerings that were then bundled up.

At 7am, we left the school room (one of the only cement structures in the community) and walked out onto the Bolivian altiplano. It was beautiful, almsot like a magical or surreal movie with muted colors that made the outlines of the buildings almost shimmer. We walked 20 minutes down a dirt road, past herds of llama and mud and grass houses until we reached a large clearing filled with hundreds of Aymara people huddled around bonfires made of the offerings with wishes we (and they) had made before. Then as the sun came over the mountains for the first time, everyone through their hands in the year and shouted "jallalla!" which more or less means "may it live" in Aymara. It was an extremely powerful experience.

Cesar and I came back to La Paz, having slept 6 of the past 70 hours.

On Sunday morning, Cesar left for Lima and Paul and I left for a 19 hour journey to Sucre. Despite my memory foam travel pillow, it was a pretty painful journey. Here in Sucre, we´ve taken two days off from work and are walking around this pretty, colonial city. It´s very different from La Paz, including politically: there is lots of graffiti on the walls that states "Evo Asesino" and "Sucre de pie, campesinos de rodilla" (basically meaning that Sucre will squash/kill Bolivian campesinos). It´s intense, and probably best that Paul and I don´t mention our politics. There is graffiti in La Paz that says "Sucre, the capital of racism" (because Sucre wants to be Bolivia´s capital again) and I think that statement is not entirely untrue.

The conference of women leaders from all over Bolivia begins tomorrow here in Sucre, and I´m excited to go. A lot of it will probably be in Quechua, but will be very interesting none the less. We will know a few of the women there from our work in El Alto/La Paz so it will be good to have some friends.

From the colonial walls of Sucre,

Nicole

Saturday, June 21, 2008

Miners,Blockades, and 1,000 Indigenous Women Leaders

As we walked toward our final Thursday interview, we mused over the possibility of going to Sucre instead. The interview was to be with the national director of Bartolina Sisa, the largest organization of Bolivian women leaders. Earlier in the day, we had debated whether or not to pursue this particular interview, since the person that seemed a better interview subject was lower on the totem pole, but focused specifically on El Alto. When we talked to her, however, she told us she was busy getting ready for a big trip, and could not meet with us for another two weeks. She did not say where or why she was travelling, and there was no reason to ask.

We decided to interview the national director. Upon arrival, she all business and eager to give us what we needed so we would be on our way, as the office was a flurry of activity. We asked what was going on and they explained that they were in the final stages of organizing a gathering of 1,000 women leaders.... in Sucre.

Pause.

Nicole and I turned to look at each other, and exchanged faint smiles. There was no need for discussi0n.

"So that is why we are so busy. Now, how can I help you?"

"Yes, well, we are here to request permission to attend the gathering in Sucre."

One hastily scribed letter of introduction later, we got our participant badges, and we are on our way. Sunday morning Cesar departs for Peru, and Nicole and I head for Sucre.

Hopefully we can learn Quechua by the time we get there.

Thursday, June 19, 2008

Photos!

Downtown La Paz. Double-clicking on each photo will let you see a great deal more detail in each image.

Pablo, César, and Nicole at Dumbo's restaurant, a place characterized by great Bolivian food and, as you might guess, a large flying elephant. The latter seems to keep all non-Bolivians at bay, as they perhaps can't imagine a place named after Dumbo meriting their attention.

Pablo, César, and Nicole at Dumbo's restaurant, a place characterized by great Bolivian food and, as you might guess, a large flying elephant. The latter seems to keep all non-Bolivians at bay, as they perhaps can't imagine a place named after Dumbo meriting their attention.

Mujeres Creando, our anarcho-feminist home away from home. The building is named "Virgin de los Deseos" (Virgin of Desires).

View of La Paz from up in El Alto.

View of La Paz from up in El Alto.

Wednesday, June 18, 2008

"Man, I feel like a womyn"

Just another 20-hour day in Bolivia (14 hours of work, 6 hours of play). Yeah, that whole balance thing is going really well. It began with our usual breakfast feast of freshly baked empanadas (meat or cheese), salteñas (the sweet and messy breakfast version of an empanada), apple strudel, juice, coca tea, and a whole bag of the same (unheated) to carry with us to El Alto to eat on the hoof for lunch. A thousand vertical feet later we were careening through our fourth day of blitzkrieg fieldwork. At the (Women's) Citizen Action headquarters, our delightful contact and now friend Norah Quispe met with us for the third time and, as she was not entirely satisfied that we were talking to the right people, took the liberty of calling them all up and inviting them to come meet with us all in one place at the same time. Quite the gift. By today (Thursday) we had already begun to follow up with individual interviews with several of these community leaders, but having them all come to us at once was a huge time saver, as we only had to explain ourselves and win their trust once (which is more time-consuming in Bolivia than in Peru or Ecuador, chiefly because the Alteños have had such a brutal time and have wisely learned to trust slowly). When the tape recorder comes out, the eyebrows go up. Just wait until we try the iPod/iTalk digital recorder!

Our meeting with the Colectivo de Mujeres (Women's Collective) was extremely powerful. Beginning in May 2003, these women have organized themselves in protest of the sale of natural gas, stating that it threatens the future of their children. They worked hard to inform the public about the issue, putting flyers under doors and putting up graffiti slogans in the dead of night. Slowly, Altenos (people from El Alto) began to realize the significance of the sale of natural gas (and natural resources in general) and how it further threatens Bolivia's ability to be an autonomous nation. The actions of the women (along with other groups such as the FEJUVE and the COR) resulted in the famous mobilizations of October 2003, during which time all of El Alto worked to shut down both El Alto and La Paz. During this time, about 80 Altenos were killed by soldiers, there was very little food, and no access to medicine. Many of the women of the Colectivo received threats and one woman was almost beaten to death by an angry mob. In the face of vast repression and scarcity of much needed resources, the citizens of El Alto banded together, creating community food kitchens in order to feed the children and using ingenuity to fight against the attacking soldiers. We learned of how the women from the Colectivo made their own bombs and how people brought whatever they could think of into the streets in order to make blockades.

At the end of October, after a month of community resistance against natural resource exploitation (and a terrible government in general), President Sanchez de Lozada fled from the national palace to the U.S.

I think we all left feeling extremely overwhelmed at the power and intelligence of these seemingly harmless women. Exploitative governments, watch out!

It was a full, long day, and we already had an evening full of plans ahead of us when Norah invited us to the Sagrada Coca dance concert. Sagrada Coca is a group of women from La Paz who do traditional Aymara dances and play music. The performance included interpretations of the various traditions used to greet different seasons. At the end of the concert, we went on stage and danced with everyone. Very good fun.

After the Sagrada Coca show, we went to dance salsa (mixed in with techno and dancehall music) at a bar that was full of tourists but still a very good time. We left at 2:15am to Shania Twain singing "Man, I feel like a woman." Indeed, indeed.

Wednesday: Making Lemonade from Lemons Requires a Decent Night's Sleep

So, after four fantastic days of fieldwork, we more or less met our match with going to sleep at 3 am and getting up at 7 am. Today's fieldwork actually had some great successes to it, including our most emotionally profound interview yet (involving state and para-military violence), but overall I'd say it took us 10 hours to get 5 hours of work done, instead our usual reversal of those figures. A lot of little things went wrong, like failing to tape part of an interview, wasting time waiting for people because we neglected to call and confirm an hour ahead of time (which no one expects, but it is the only way to make things happen on time), and a few other minor but time-consuming mistakes. In our style of field work, this kind of thing happens a dozen times a day, but the difference is that usually we are mentally sharp, proactive, and inventive about making maximum use of our time even though things rarely go as planned. But today we were all too tired and we just kind of waited for the world to come to us -- and it never showed up -- so we eventually chased it down (slowly).

Our final appointment of the day was to present ourselves at the Regional Workers Central (COR) of El Alto council meeting. This was our official opportunity to ask permission to begin interviewing COR leaders, have the blessing of the COR leadership, and get contact information. Of course, we've already completed interviews with three COR leaders (we're not very patient), and wheedled our way into 90% of the contact info we needed, but it was still an important moment. As I stood up before the assembled leaders at 5:00 pm, I momentarily calculated how many of the 34 hours I had slept (four) and wondered exactly what would come out of my mouth given that my fluent Spanish has collapsed down to Spanish 101 levels during the last couple hours due to lack of food. But, I've done an awful lot of these speeches for groups in Lima and Quito, and this wasn't much different except for the intensity of the Q&A. They seemed to like my answer to their critique of the role of the United States in supporting economic and political violence in Bolivia (I explained that their vision of the U.S. government was far too limited and that the civil liberties and human rights of thousands of people in my own country and community were also under siege).

By the end of the meeting they were floating proposals for how to gather everyone together for rapid-fire interviews of all the 51 leaders (it sounded like speed dating, but with social science), which we declined, since we only need to talk to about 12 of them, and each in depth. But it was fun seeing them enthusiastically jumping on board.

In another week we'll be joined by documentary photographer James Lerager, who worked extensively in Bolivia on the 2005 Evo Morales presidential campaign, but who has not yet worked in El Alto. We expect his high-tech camera will evoke suspicion and fear among some of our subjects, but I called James tonight and told him to bring a sure-fire calling card: a great pic of James and Evo mugging for the camera on the campaign trail. I think that will about cover it!

Monday, June 16, 2008

No, we don´t work for the CIA

We first went to the headquarters of the Central Obrero Regional in El Alto (COR- the Regional Workers Central), a group with a half million members that was very active in a massive mobilization in October 2003 that succeeded in overthrowing a corrupt and neoliberal president (Gonzalo Sanchez de Lozada) who essentially gave away Bolivia´s natural resources (and is currently happily residing, despite numerous requests for his extradition, in Chevy Chase, Maryland). The COR is a very powerful organization in El Alto (everyone we talk to tells us to go speak to them), and 8 of its 51 directors (drawn from various federations, unions, and associations) are women. As we are focusing on the role of female leaders with popular movements that focus on non-gender specifics issues (such as for the control of natural resources), so far the COR seems to be a perfect case study for our research. Plus, an important part of their agenda focuses on re-taking control of privatized natural resources, so the group is an excellent fit in that respect as well.

We walked into the headquarters and received a warm reception by some of the directors of the COR. They were definitely curious and perhaps a bit skeptical of us at first, but that really only lasted 5-10 minutes before we won them over. For two hours, we then learned about the current goals of the COR (defend Bolivia´s natural resources, stop sending natural resources to the enemy nation of Chile, have ex-president Sanchez de Lozada extradited to Bolivia, recuperate what was privatized, and rid Bolivia of neoliberalism) as well as the internal governing structure. The COR doesn´t have a budget- its leaders work organizing the group, as presidents of their union/association/federation/etc, and also have jobs (as nurses, teachers, butchers, transit employees, etc) in order to make money. We set up meetings with some of the female leaders of the COR and are also going to their weekly directors meeting (with all 51 people present) on Wednesday. Clearly, we left the COR´s office very excited and eager to continue with the fieldwork.

Our next stop was FEJUVE (Federacion de Juntas Vecinales de El Alto- Neighborhood Federation of El Alto. They are also active in the nationalization/anti-neoliberalism movement in El Alto)... but this visit went very differently. We were immediately granted a meeting with the president of the FEJUVE, along with several of his supportive minions. But instead of an eager reception, we were immediately questioned (interrogated) on our connection to the US government, neocolonialism, what we were going to do for them (including one audacious request for a specific budget on how we might help financially) , that the US government was going to use the information they gave us against the citizens of El Alto... basically, that our research is the handmaiden of colonialism.

Fortunately for them (but perhaps unfortunately for my personal sense of morality), Cesar, Pablo, and I all agree with those criticisms of Bolivia´s history of exploitation, the role of the US government in fostering unrest in Bolivia, and the tendency of NGOs and academics to gather information and never give anything back to the community. They seemed fairly satisfied with our activist credentials, bolstered by our social justice projects that continue in Peru long after the academic research was done. We worked hard to make our opinions clear, and must have passed the test because we were invited to come back tomorrow for a real interview.

As a side note, my favorite quote (stated by a key member of the FEJUVE) is that the "Czechoslovakian" immigrants in Bolivia are all "cobardes y maricones." ...oh lord.

In some of our other interviews from last week, one thing surprised me: in some ways women leaders of women's organizations did not want us to study women leaders of non-women's organizations. There was a sense of "why do you want to focus on those women leaders when the most important and effective ones lead groups focused specifically on women?" But we're sticking to our plan of focusing on the women leaders that pretty much get ignored by most studies.

J'allalla! ("may it live" in Aymara)

Nicole and Pablo

Saturday, June 14, 2008

Reflection on Nicole's collaboration

All true. But really, that's only the beginning of the abrupt transition Nicole has experienced the last 5 days. She's gone from 102 degree humidity to very dry and sometimes below freezing. From near sea level to 13,000 feet. From an English enviroment to 95% Spanish. From a house full of comforts to a backpack. From vegetarianism to carne, pollo y cerdo. From a peer group she knows and trusts to a group that, except for me, are all new people to her, and people that already have worked together for 7 years -- she is the only newcomer. And she has had to drastically recalibrate her relationship with me, going from office, library, and email collaboration to sharing daily supplies, every meal, and most hours of the day.

That is a massive transition.

Which is why I'm so delighted that Nicole is veritably bounding through it (albeit with breaks for oxygen between bounds -- this city is high -- so high that Nicole battled an Old Faithful-level geyser of a nosebleed this morning). At our first research team meeting a couple days ago, she jumped right in proposing a schedule for the following day's fieldwork -- and no one even asked her to! Cesar and I added our input and it was done.

Here are just a few obserations I jotted down in my notebook a couple days ago on how Nicole's collaboration is making our group function better:

1) Building a strong team dynamic. Through her participation in Macalester's Lives of Commitment program, Nicole has come to value reflective and intentional community building, and at her instigation we began a daily team meeting, which is usually right after dinner. This was Nicole's idea, but the basic structure is based on the Montessori group trip model pioneered by Doug Alecci and Lake Country School. First we talk about what we did and learned during the day, with an emphasis on things that went well and positive experiences. Second, we discuss what needs to be improved, including conflicts within our group. Third, we plan out the next day, with an eye to building on whatever we learned from the first two parts of the meeting. Finally, we conclude with thank-yous and compliments.

2) Nicole keeps us on schedule. I grew up a house where if it took you 17 minutes to get somewhere, you left 17 minutes before you wanted to arrive, and you were neither early nor late -- just right on time. At least this was my Dad's approach. It drove my Mom crazy. I take after my Dad on this one.

A not atypical exchange between me and a flight attendant: "Am I at the right gate? I don't see any people." "That's because they're ALL already on the plane... waiting for YOU."

Yet I've never missed a flight, which just seems to encourage me. But Nicole won't have it. Killing time during our Miami layover, I wanted to hike one last stretch of beach, but she insisted we head back, and a good thing since it took three slow buses to return to the airport (and we were hardly willing to spend $32 on a cab). Nicole is good at focusing on what needs to get done and keeping things on task.

3) Keeping me/us in check. Nicole and I are intense people and we approach most things in our lives with a lot of intensity and not much balance. It's part of why we were drawn to work together. My extreme nature manifests in most arenas of my life (work, play, politics, health, relationships, spending habits, itineraries, values and ethics, correspondence, and much more). This pretty much worked fine until I became a parent, at which point it all pretty much imploded. In 2007-08, Nicole and I each (separately) realized we needed more balance in our lives (she's 13 years ahead of me on this one). But while I'm still in a bit of denial, she's clearly more accepting of this reality and is assertively and helpfully insisting that Cesar, she, and I all do such radical things as eat regular meals, sleep relatively normal hours, take breaks during the day (gasp), and even (shudder) take the occasional day off.

All told, just five days into our time abroad, Nicole's essential contributions to making our research team function better are already evident. But... do we have to take breaks?

--Paul

Friday, June 13, 2008

Brilliant first day of fieldwork

--Pablo

Friday:

The air in El Alto is thinner, colder, more polluted. As our little bus wound up the Andes on route to El Alto (about a 17 minute ride from La Paz), my ears popped in time with the bus attendent shouting the destination of the bus at rapid-fire speed out the window (Lacejalacejalaperezlaperezlaceja). In El Alto, the Andes poke out from behind the buildings, snow peaked and looming, reminding me that at 13,000 feet it´s normal for my heart to be continually beating so quickly.

We had a very succesful day of interviews in El Alto, using information gleaned from various conversations yesterday. We went to the headquarters of an organization called Gregaria Apaza, which works to promote the empowerment of women and families in El Alto. They work with NGOs throughout all of Bolivia, have a radio station called Radio Pachamama, have legal services, clinics for victims of abuse, have job training clinics, and much more. We spoke with two women who work in a sector of Gregoria Apaza called Accion Ciudadana (Citizen Action), promoting women in popular organizations and social movements. The conversations were very helpful in understanding important organizations in El Alto, how they function, who is involved, what are problematic components, etc. Not only was the information really interesting and helpful as we begin to focus our studies, but they were also my first field interviews!

Back in La Paz, we interviewed a city councilwoman who said she will put us in contact with politically active women- and then went out for pizza.

And we are going to move residences! Until now, we have lived in what Paul dubbed the ¨Gringo Ghetto¨- filled with hipster tourists with expensive gear, an atmosphere that is beginning to be quite oppressive for all of us. Tomorrow we´re moving to a hostel located in the headquarters of an organization called Mujeres Creando (Women Creating), an anarcha-feminist group that tries to radically smash patriarchy. It should be a very interesting, and welcome, change. http://www.mujerescreando.org/

I welcome you to also smash patriarchy,

Nicole

Wednesday, June 11, 2008

Complementary Collaboration

So before getting to the black market mapmonger hawking illegal street-by-street maps of El Alto to an odd trio of peruano and estadounidense social scientists, let´s back up a bit.

Our departure for Bolivia, Peru, and Ecuador prompted us to create this blog in June 2008, but really this 64-day Andean adventure is the centerpiece of a multi-year project that began more or less in Nicole´s first month of college (Sept 2006) and will conclude a bit before she graduates in May 2010.

Yes, I do tend to plan ahead.

So what exactly are we doing? I guess it´s principally an original hybrid of fieldwork-based scholarship, bi-lingual civic engagement in the Americas, and radically egalitarian collaboration.

I´m sure that clarifies things perfectly.

The following excerpt from one of our three grant proposals (we found out three days before our departure that we got all three grants) will hopefully do a better job explaining what this is about. Nicole claimed green, and I got purple, so I guess black is now the official font of jointly-written text. Not sure what color Cesar will choose when he posts...

This project attempts to stretch the boundaries of faculty-undergraduate collaboration. In order to include the student collaborator at all stages of a multi-year project, the partnership emerges earlier in the undergraduate’s college experience than is typical—as early as her first semester and no later than the sophomore year. Thus, full-fledged faculty-student collaboration occurs at every stage of the research process: project conception, literature review, research design, grant-writing, intensive fieldwork, conference presentations, journal submission and revision, and publication of a co-authored article.

Given the scope of our planned activities and outcomes, a casual observer may find this project ambitious because it involves an undergraduate in an unusually broad array of exciting experiences. But at the core of the project is a boldly innovative approach to faculty-student collaboration that we hope will contribute to the ongoing transformation of faculty-student relationships and learning at Associated Colleges of the Midwest colleges and beyond.

Among scholars of pedagogy and educational philosophy, the “empty vessel” or “banking” approach to education—wherein the teacher has all the knowledge and the student is the eager receptacle—has been largely discredited, but in the realm of faculty-student research this approach remains commonplace. It is generally assumed that the faculty member has the full skill set needed for the task at hand, and the student, though she will certainly make an important contribution, is considered an apprentice who is primarily participating in order to learn, rather than to contribute.

With this project, we are attempting to challenge this model and pilot a new “Complementary Collaboration” approach that is marked by three distinctive elements: 1) the emergence of an egalitarian relationship; 2) complementary skills; and 3) collaborative engaged scholarship.

The Emergence of an Egalitarian Relationship

Given the project’s collaborative aims, an egalitarian faculty-student relationship is clearly essential, but equally important is the manner in which this relationship emerges. Egalitarianism cannot be handed down from a faculty member to a student. Paul Dosh has tried this with other students, but ultimately it proved to be something less than egalitarianism because “inviting someone up” (from student to junior colleague) is not the same thing as building together from the ground up.

The academic relationship between Nicole Kligerman and Professor Paul Dosh began in a traditional fashion, but has burgeoned over two years based on shared common interests, both academic and personal. As a member of Paul’s first-year seminar, “Latin America Through Women’s Eyes,” Nicole explored her interests in social movements, feminism, civic engagement, and Latin America with Paul’s guidance. Based on shared academic interests, as well as a personal conviviality, Nicole worked with Paul the following semester to help him prepare his book for publication and to pursue an independent study. Utilizing their complementary skills and abilities, they learned from each other to create an egalitarian academic environment based not on sameness, but on diverse talents and perspectives. Thus the current project on Bolivia and Ecuador was born from the intersection of academic interests, a long-standing egalitarian working relationship, and complementary skill sets and backgrounds, all of which help ensure the true collaborative process of their research.

Complementary Skills

In 2007, Paul Dosh directed the Chuck Green Civic Engagement Fellowship, which is predicated on the assumption that non-specialized liberal arts college students are better positioned to accomplish many civic engagement projects that older and more experienced—but highly specialized—faculty. Faculty are experts in their field, but such specialization can be a liability when they need to access information, networks, and resources that are outside of their specialty field. Undergraduates, though often not yet experts at anything, are potentially capable of everything. Under Paul’s supervision, the 2007 cohort of Chuck Green Fellows accomplished amazing summer civic engagement projects, in part, because the fellowship helps the students see how ideally-suited for the task they are—even better suited than their faculty mentors!

Expanding upon this understanding of research and engagement, our project draws upon the complementary skills of both Paul Dosh and Nicole Kligerman. Some skills are gained from years of research experience; Paul is an expert at field interviews and he will need to teach Nicole how to interview social movement leaders. But Paul is now a specialized political scientist whose professional activities are increasingly focused, suggesting that Nicole’s fresh record of civic engagement and service will help broaden the project’s impact beyond a narrow audience of academic experts, to include non-academic communities in the Americas.

Collaborative Engaged Scholarship

ACM colleges are increasingly focusing on the interplay of scholarship and civic engagement, and it is important that our collaborative model contribute to this positive trend. This project seeks to reach multiple audiences (in two languages), including the communities and popular movements that we plan to study. Thus, just as the skills of faculty and student complement each other, the demands and benefits of scholarly research and civic engagement complement each other as well.

At present, most civic engagement projects are either: 1) faculty-initiated, with students participating; or 2) student-initiated and student-completed, either as a class assignment or as part of a student-run organization. Much less common are civic engagement projects that are co-initiated by both faculty and students, outside the framework of an academic class. It is important to us to contribute to this fledgling, but vital new category of civic engagement projects.

The term “complementary collaboration” ought to be redundant, but given the standard contours of most faculty-student collaboration, genuine complementarity often proves elusive. Grounded in an egalitarian research partnership, complementary skills, and collaborative engaged scholarship, we anticipate that we will both generate a better understanding of popular movements in Bolivia and Ecuador and also show how this superior understanding would likely not have been discovered by a faculty expert working alone.

So I guess that´s a description of how we are pursuing this project. The details of what we are pursuing and what we expect to come out of it will have to wait, as my fingers are getting numb from working on a keyboard that is, basically, outdoors in the quite chill mountain air. But so far, I think we are off to a great start!

--Pablo

Tuesday, June 10, 2008

Bienvenidos a Bolivia!

At Miami Beach, we stumbled into a superswank hotel and met a very earnest and eager bartender who eagerly asked about Paul´s hardcore hiking boots and, upon hearing where we were going, asked if we are missionaries. Even though we had to decline on the missionary title (although we are on a mission, of some sort), the bartender told us we were "living the dream." Heck yes!

There are posters at bus stops all over Miami that advertise for Sunglass Hut and state "I miss food I can actually pronounce." I was and am bowled over by the xenophobia and nativism of that statement. But the people in Miami were very friendly and helped us greatly to get on a total of 5 city buses before returning to the airport.

Our flight from Miami to El Alto (the city right next to La Paz) was filled with real missionaries with bright red shirts that had their budget printed on the back. (Trip=$1900. Immunizations=$300. Passport=$75). That sure is a good way to not look like a conspicuous and consumptive tourist... The flight was pretty sleepless (despite my memory foam travel pillow), but we landed in El Alto alive and well.

The cab driver who took us from El Alto to the Rosario neighborhood in La Paz, where we are staying for now, told us about a huge civil strike and march that took place in El Alto the previous day. He said "at least 50% of the population" stormed the US Embassy building in protest. That figure might be an exaggeration, but here's an article from Upside Down World about the protest so you can learn more: http://upsidedownworld.org/main/content/view/1321/1/

The altitude and cold of La Paz are no joke. Despite taking altitude medicien and chugging water throughout our time in Miami, I can definitely feel the thinness of the air. I don't feel sick, but light headed and out of breath. The air is very thin- when the plane landed, it barely went through the clouds. It's also cold (it was 30 degrees when we landed this morning!). I go from -40 degree Minnesota winters to 102 degree Philadelphia summers down to 30 Bolivian winters.

But no matter- so far everything's great. We're living in a cute little hostel for the next few days until we decide where it would be most convenient for us to live so we can be close to our research sites. The very steep cobblestoned streets are filled with honking cars, cholita women in large pettycoats with two long braids, and the occasional hipster Israeli tourist. We met some of Paul's friends (along with their friends) for a delicious Cuban lunch, and this afternoon Cesar Flores, a social scientist from Lima who will be living and working with us for the next two weeks, arrived to La Paz from Peru.

So we officially begin! We'll be holding initial interviews over the next few days in order to firm up the contours of our project, which should be exciting. And tonight we're going salsa dancing! I'll post pictures when I remember to take them.

With a light headed farewell,

Nicole

Monday, June 9, 2008

"Get out of the library!"

Well, this particular summer excursion and research trip has taken about... 20 months of preparation, but we are indeed about to get out of the library and into the field, and I'm really excited about many things. Still, the last 24 hours have been more about who I'm leaving behind for these initial weeks, rather than what I'm looking forward too. Andrea and Araminta are excited to join us in Ecuador in July, but until then, five weeks is a really long time for me to be away from my family. Araminta, now 2 years and seven months old, has never been away from her Papa for more than two weeks, and Andrea and I have only been apart for such a long stretch once before in our 12 years as a couple.

I'm really excited about our core research project, as well as our multiple side projects (there are always a lot of those!), but for me it's always about the people. It's been a mad task coordinating the schedules of our Peruvian collaborators Jesús and César, our camera-clicking Californian James, Nicole, and the whole Dosh Galdames clan, but it's finally all set, and I'm delighted to be working with this amazingly talented and competent team. I've done fieldwork with all of them before except Nicole, but Nicole and I have been working together since her first day of college in September 2006, so in some ways I've worked more with her than some of the other team members.

The first couple weeks, which may be the most intense of the trip, will be just Nicole, me, and César in La Paz/El Alto, so I've been pretty focused on that. We'll meet up with Dave Holman (Carleton class of 2006) and Rommy Cornejo Diaz on Tuesday in La Paz, who, tragically, have decided to welcome us back to Bolivia by taking us salsa dancing. Somehow I will endure.

Lots more to write, but Andrea and Ara are ready to take me to the airport. Wow, it's finally happening, after so many hurdles and twists and turns. ¡Vamos! Time to get out of the library.

--Pablo

Sunday, June 8, 2008

This time tomorrow

To say that I'm 100% full of excited bliss would be an overstatement. As per usual, I'm overthinking (what if our bus falls off the side of the Andes?), checking my packed bag millions of times for the 4 sticks of Chapstick I've carefully packed, and attempting to take calming, zen breaths as my heart races. I'm trying not to make preconceived notions of what this research project (in both outcome and methodology) will be like, instead attempting to be open to the infinite possibility of living for two months with new people in a new place. How our collaboration and egalitarianism will take shape surely will be an interesting process...I'm open minded and excited for all that's to come, but I would be lying if I said I wasn't nervous.

Coincidentally, the song "This Time Tomorrow" just came onto my computer as I write this. "This time tomorrow, where will we be?" the Kinks ask me. We'll be in the sweltering heat of Miami in the literal tomorrow, but in the figurative sense of tomorrow, who knows?

We plan to update this blog on a regular basis, allowing for our family, friends, and whoever else to follow along with our Andean adventures, research project, and reflections. Paul and I will take turns writing (he's excited to write in purple, of course) and hopefully will be able to update it on a regular basis. I hope you enjoy it!

From the humidity of suburban Philadelphia to the 37 degrees Fahrenheit of La Paz, Bolivia,

Nicole